5 Filmmaking Choices To Elevate Your Project

I can’t help but “talk shop” when I’m in a room with other filmmakers; especially cinematographers. We often talk about their camera of choice. What they like/don’t like. What lenses they use. Specific lighting techniques from their most recent projects. But if you’ve spent a lot of time in film and video production, you know that the quality of your image isn’t only about the camera.

The difference between a film that looks “good” and one that feels “great” is found in the quiet, intentional choices made behind the lens. It’s the difference between simply capturing a scene and communicating an emotion.

Here are five underrated cinematography techniques to help you move beyond the basics and elevate your visual storytelling.

1. The Power of the Lingering Glance

In modern video, there is a tendency to cut as soon as a line of dialogue ends. We are so afraid of losing the audience’s attention that we rush the rhythm. However, great cinematography understands the power of the “extra” second.

The Technique: Instead of cutting immediately to the coverage, hold on the subject for a beat after they finish speaking. This allows the audience to see the character process the moment.

The Example: Look at Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (Lensed by Yorick Le Saux). The camera often lingers on Jo or Beth just a second longer than “necessary,” turning a simple conversation into a profound character study.

Watch this video from Every Frame a Painting to see this example in action and how it affects an audience’s emotion.

2. Expressive Framing and Subtext

Good cinematography follows the Rule of Thirds. Great cinematography uses composition to tell the audience how a character feels about their world.

The Technique: Use “Short Sighting” (framing a character so they are looking toward the edge of the frame they are closest to) to create a sense of claustrophobia or being trapped. Conversely, use “Lead Room” to show a character with a future or a path forward.

The Example: In Mr. Robot (Lensed by Tod Campbell), the framing is notoriously unconventional. Characters are often pushed to the extreme bottom corners of the frame, visually representing their isolation and the overwhelming weight of the society around them.

3. Motivated Movement vs. Stillness

One mistake filmmakers can make is moving the camera just because it can move. If the camera is moving, it should be motivated by the energy/emotion of the scene. This doesn’t mean that you should lock off the camera every time your character is still and contemplative. Nor does it mean the camera should be moving every time the emotion of the scene feels chaotic and frantic. But whatever you choose, make sure that choice serves the scene and the story.

The Example: Compare the work in 1917 (Lensed by Roger Deakins), where the constant movement is a literal manifestation of the protagonist’s relentless journey, to the calculated stillness in The Bear (Lensed by Andrew Wehde) during the high-tension kitchen monologues. When the camera stops moving in a show that is usually frantic, the audience leans in.

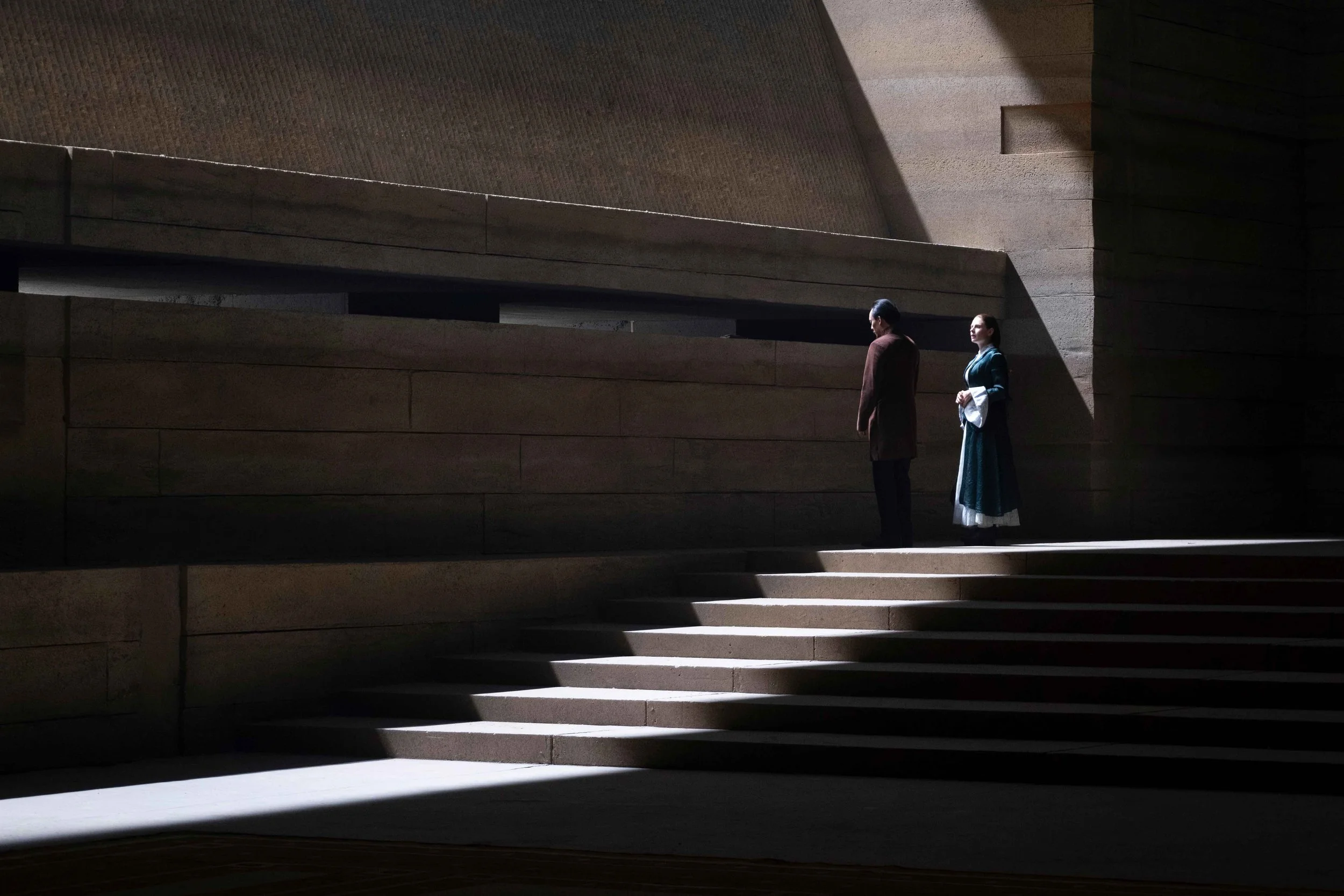

4. Shadow Play: Lighting for Emotion

We often spend so much time trying to “fix” shadows that we forget they are our best storytelling tools. Sometimes, the shot isn’t about seeing everything; it’s about choosing what to hide.

The Technique: Use “Negative Fill” (placing a black flag or fabric on the side of the subject opposite the light) to deepen shadows. This adds shape to the face and creates contrast.

The Example: Dune (Lensed by Greig Fraser) is a masterclass in this. Despite being set on a desert planet with “bright” sun, the interiors and even many exteriors use deep, rich shadows to create a sense of mystery and ancient power.

5. Intentional Depth: Tracking vs. Parallax

As discussed in a previous post, movement through space changes the viewer’s perspective. But the choice between a tracking shot and a parallax shot is a narrative one.

The Technique: Use a lateral tracking shot (parallel to the subject) to observe a world as an objective outsider. Use a parallax shot (counter-panning while moving) to isolate a character and create a subjective, three-dimensional connection.

Whether you’re shooting a corporate testimonial or a narrative short, ask yourself: What is this shot trying to say? Use intentional choices to bridge the gap between a viewer who is just watching and a viewer who is truly feeling.